Becoming Human

BY SARAH ELKINS

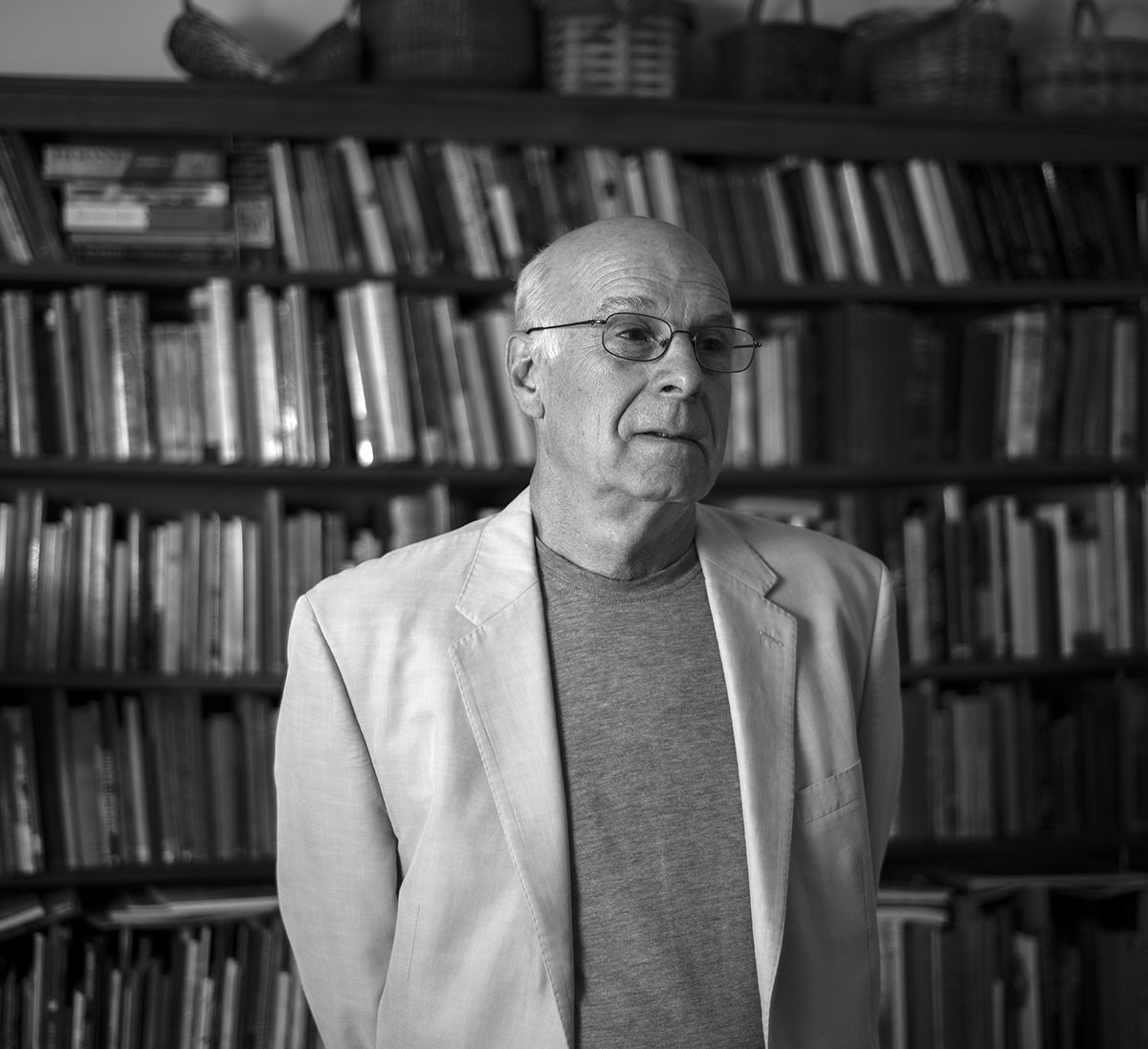

“We’re modern Indians; we have a dishwasher,” Larry Two Rivers Brown jokes as he sits down to dinner with his wife, Shelly. Larry’s mostly grey hair is loose and hanging to below his shoulders. His face and hands are browned from working outside. He’s been repairing fences all day on the farm where he grew up. He smiles frequently and moves quickly between jokes and quiet nostalgia.

I sit down at the dinner table where the couple is having stuffed peppers and fried potatoes. Shelly offers me a plate, but I explain I’ll be too busy writing (I prefer to take notes instead of recording conversations).

Larry looks at his plate, “Man, we could have had woodpecker dumplings if I’d known you’d be writing about this,” he says, “Or, groundhog is good this time of year.”

I ask what woodpecker dumplings are. The only explanation I get is, “There isn’t a whole lot to a woodpecker. You chew on what little meat there is.”

Larry Brown is a descendent of the Cherokee Indians who once lived among the mountains and caves of Appalachia. The word “Cherokee” an English-language adaptation of “Tsalagi,” means people who live in caves. Both his fraternal and maternal grandparents, on the Brown side, were Cherokee. In the 80s Larry began researching his lineage, seeking to learn and preserve the heritage that had only been whispered about within his family.

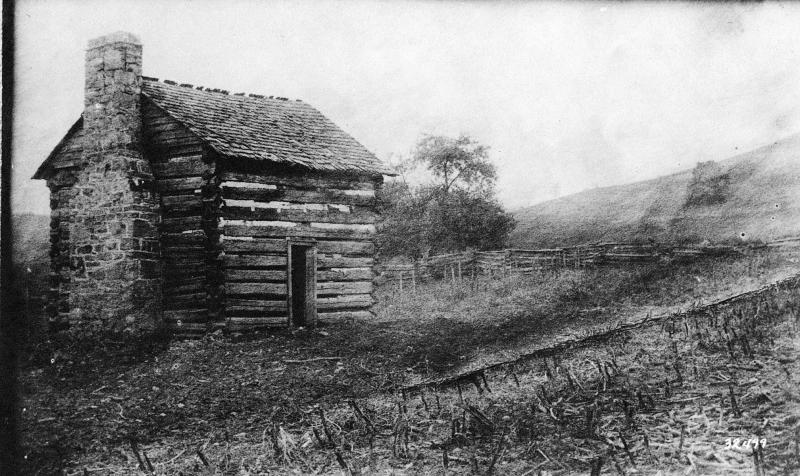

His grandmother, Dorothy Elizabeth Lawhorn Brown, used to say to him, “We’re ‘churkey inding.’” Larry remembers how all her words came out in two syllables. Cherokee became churkey, and Indian became inding. She was the only member of his family willing to talk about the family’s Cherokee roots. Like many of the native people living throughout Appalachia, being of Indian descent was a fact to be kept secret or denied. Until 1964, Indians were not allowed to own land in the state of West Virginia. As late as 1950, native people living in West Virginia were still being relocated to reservations in Oklahoma.

Larry is sixty years old, so his grandparents, farmers by trade, certainly had good reason to keep silent. But, Dorothy Brown quietly shared her traditions with her grandson. He recalls her healing songs. At the age of 16, Larry had a debilitating migraine. Nothing seemed to alleviate the headache, so she led him into a dark bedroom. There his grandmother sang a healing song and waved her hands over his body.

Larry stands to illustrate. “She never touched me, just waved her hands over me like this,” he says, holding his long arms out in a slow, wafting motion. “Then, I dozed off. I’ve never had a migraine headache since.”

He continues, “When I was a child, I used to get these little seed warts on my fingers. She charmed them off. I can’t tell you what she did though or they might come back.”

While there is no federal or state recognition of West Virginia Indian tribes, in 1982 Larry began the attempt to prove his own Cherokee lineage. In order to do so, an individual must prove familial connection to a person listed on a document known as the Dawes Rolls. Established in 1893 by the US Congress, the Dawes Commission, sought to negotiate land trades between the “Five Civilized Tribes of Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole” and the US government. In return for control of tribal lands, approved Indians were given land in Oklahoma. At that time, approximately 100,000 out of 250,000 applications to the commission were approved. The list of approved individuals became known as the Dawes Rolls and they are still used today as the basis for proving tribal affiliation.

For the next four years, Larry worked to prove his own connection to a Brown listed in the Rolls. Then, in 1985, he gave up. Because so many generations refused to talk about or hand down their native heritage for fear of persecution, proving a connection to the names recorded at the end of the 19th century becomes impossible. Larry shakes his head, “You know, ours is the only race in America that needs a piece of paper to be identified.” Larry began to understand that his Cherokee-ness was not bestowed upon him by a piece of paper. Instead, it was the traditions that had been handed down to him that held his cultural identity.

He explains, “In Indian tradition, the greatest gift to give is a skill, knowledge, a craft.” Walker Calhoun, a renowned elder in the Eastern Band of Cherokee, was the first to teach Larry stomp dancing, the shuffle-and-stomp style of dance practiced among many eastern woodland tribes. Calhoun, one of the most celebrated keepers of Cherokee music and dance traditions and a skilled medicine man, went on to teach Larry how to make blow guns from thistle. Calhoun died in 2012, at the age of 93.

Larry’s skills also include flute making, flint knapping, and leatherwork. He attributes Leonard Lone Crow McGann and Raymond Redfeather, both celebrated artisans, for passing on the traditions to him. For every skill learned, it is the responsibility of the learner to teach others, ensuring that the traditions remain alive. Larry presents to groups and organizations frequently.

Throughout our talk, Larry referred to himself as Indian and a red man. I asked him why he used those words instead of the more politically-correct Native American that I had always been instructed to use. He shrugged, “I guess ‘First People’ is a word that most people accept, but I’m not one of those people who gets upset about words. Most real human-being Indians are okay with those words because it keeps us alive.”

Becoming human being is something Larry talks about a lot. He likens it to what many Eastern traditions would call enlightenment. In Indian tradition, all people are striving to be human beings. In becoming a human being, a person begins to understand the importance of respecting the earth, of returning everything after it is used.

“Now, I return rocks to their places after I’ve made a fire ring. I didn’t understand that until I became a human being,” Larry says. It wasn’t until his own transformation, around the age of 36 or 37, that Larry’s Indian name, Two Rivers, came to him in a dream. Two Rivers refers to the valley of the two rivers on the farm where he grew up.

Larry carries three names: his dominant culture name, Larry Brown; his Indian name, Two Rivers, and a prayer name which is never spoken. His prayer name was made known to him on a vision quest. Of the experience, he says, “After four or five days with no food or water you really learn about yourself.”

An Indian name may change several times throughout life. He gives an example, “Geronimo was Curly before he was Geronimo. That name came later in his life.”

Larry has a sweat lodge on his farm where he conducts ceremonies, but they are not open to the public. “I am not a medicine man,” he says, “I’m not a spiritual healer. You have to be really in tune with people. I don’t feel qualified to do that.” Larry has been employed by Kroger in Fairlea, WV for 43 years, where he manages the produce department. Well, 43 years and 9 days, as of today, to be exact. “To be Indian,” Larry asserts, “means you appreciate everything. I feed people. I’ll never get rich working in a grocery store, but I do something important.”

He goes on, “We’ve become a society of people who don’t do anything. You need to work. It’s important to sweat and work hard on a simple thing.”

He thinks for a moment, “Like today in the hay fields, you could see the wind coming in waves. We’re not alone.”

That’s the way with Larry, it seems. He weaves the philosophy of his Cherokee tradition with the everyday world he encounters. He laughs about how disappointed children are when he drives up in a truck for demonstrations, and he recalls during a march in Washington D.C. when he was dressed in full regalia, photographers went berserk trying to capture a photo of him talking on his cell phone.

Larry is insistent that the simple culture of the red man is not something from another time. “The Creator does not have a clock,” he smiles. He seems to be saying we can respect the earth, live simply and drive a truck. The Creator doesn’t even seem to mind when he swipes his iPhone and asks Siri to clarify something he’s just told me.

I asked Larry about some of the other beliefs he carries. He gives a straightforward answer, “There will never be world peace until the red man is invited to sit in council.” He continues, “Each race has a calling. The red man understands nature. The white man has fire. The black man has strength and knowledge of water. The yellow man understands spirit. So, when everyone sits down to talk each race holds influence.”

In the end, the earth will shake and “rid itself of humans like a dog rids itself of fleas,” Larry says. “But nothing in native prophecy is on a deadline.”

Larry asks me, “Do you remember when my hair was very long?” His shoulder-length hair, a little more than a year earlier, hung down the length of his back. He reaches back and pulls his hair into a ponytail with his hands.

“Long hair is a gift and it’s an outward symbol that everything is going okay,” Larry stops. “My dad passed away on May 7th last year. I cut it in ceremony.”

Larry’s voice catches but he continues. On the day of his father’s death, he went to the woods on his farm and cut his hair with a hunting knife. Some of his hair went with his father. Some was given to the birds for their nests. Some was buried in the earth, and some was burned in prayer. Mourning lasted a full year, during which time Larry was not permitted to dance or celebrate.

“It’s hard to give you 10,000 years of history,” Larry shrugs. He seems unsure that he’s told me what I need for a story. “We’re so bombarded by dominant culture, he says, “with TV and media. You’re blasted with you gotta be, you gotta be, you gotta be. Just stop for the 45 seconds it takes the sun to disappear at the end of the day. Ask yourself, ‘What did you do right? What did you do wrong? What will you do better? We’re not alone.”

Larry Two Rivers Brown is a human being who repairs the fences on his farm and talks to the black snakes who visit him there. He is a grocer who knows you’re probably not going to wash your grapes when you get home, so he takes extra care. He is mourning his father and celebrating his grandmother and breathing new life into the culture and traditions that raised him up out of the valley of the two rivers.