The State Fair of West Virginia at 100

By Leah Tuckwiller | Photography Courtesy of The West Virginia State Fair / Social Bee Marketing Agency

It’s a perfect August day in the Greenbrier Valley—eighty degrees or more, a cooling breeze brushing over your face, the sun high and the air smelling of sugary-sweet fried dough. Through the traffic and the long walk from parking, you’ve made it across Route 219 and into the gates of the State Fair of West Virginia.

To one side, carnival rides whoosh and rattle, music is piped in under the high shrieks of joyous voices. Friends call to one another from across the high energy midway, between the snap of brightly colored banners overhead and the gentle wave of heat lines rising from the pavement below.

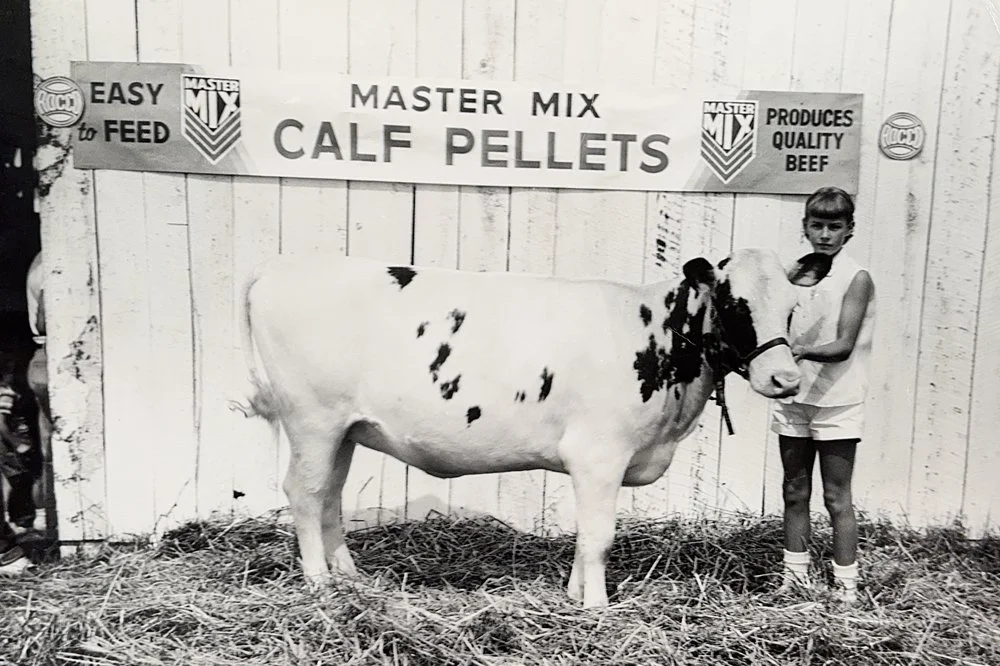

At the other end of the grounds, the rush of noise retreats a bit, giving way to the low hum of casual chatter and the pulse of the generator at the roasted corn stand. Announcers’ voices cut into arenas to direct cattle, hogs, horses, sheep, and all other manner of livestock as they take the show ring, led by hardworking handlers of all ages.

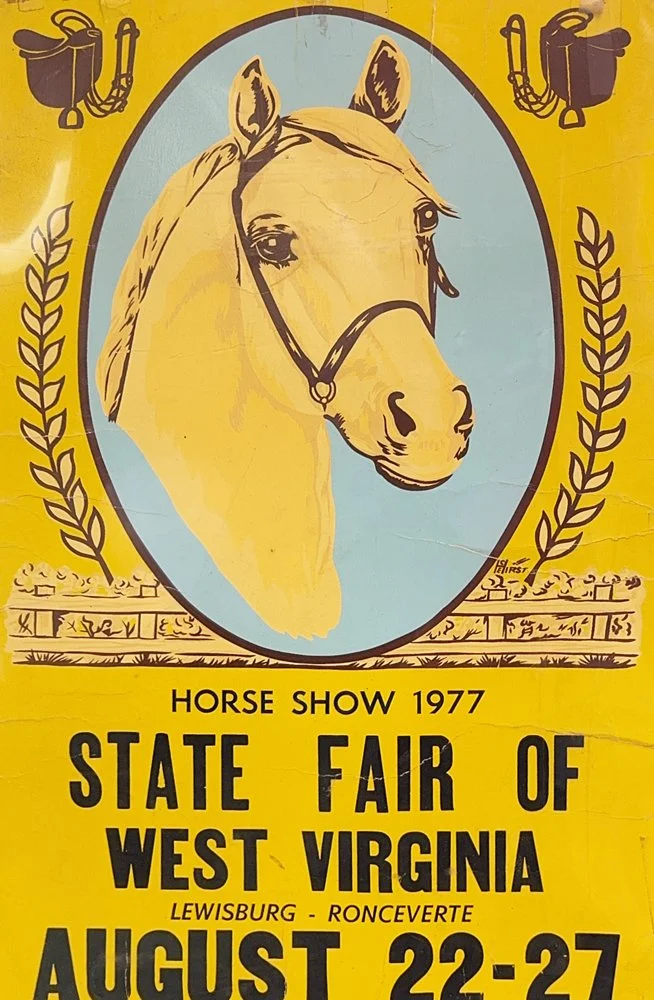

This experience has stood the test of time. The Fair organization marks its 105th consecutive year of operation in 2025, and its 100th annual event. Thirty years ago, walking into the State Fair was much the same as it is today, at least in the ways that matter. In 1922, the Greenbrier Valley Fair was formed as a driving force for agriculture and community in the area, and despite some confusion over names and timelines and locations, the beating heart of the Fair lives on.

“When people do the math, it doesn’t add up exactly,” says State Fair of West Virginia CEO Kelly Collins. “They don’t know that we had to cancel in 1941, and they don’t know that we considered the 20 years that we were known as the ‘Greenbrier Valley Fair’ in the hundred-year count.”

In over 100 years, the State Fair, across its iterations, has only been canceled for two reasons—World War II, and the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, it takes the world grinding to a halt to stop the Fair from setting up each year, but the occasional gap and a “new” name has made keeping track of the years a little more difficult than it should be. For the 90th Fair, as the staff tried to put together memorabilia like posters and shirts, they found themselves having to double-check their count.

This year, Collins has a spreadsheet to prove it.

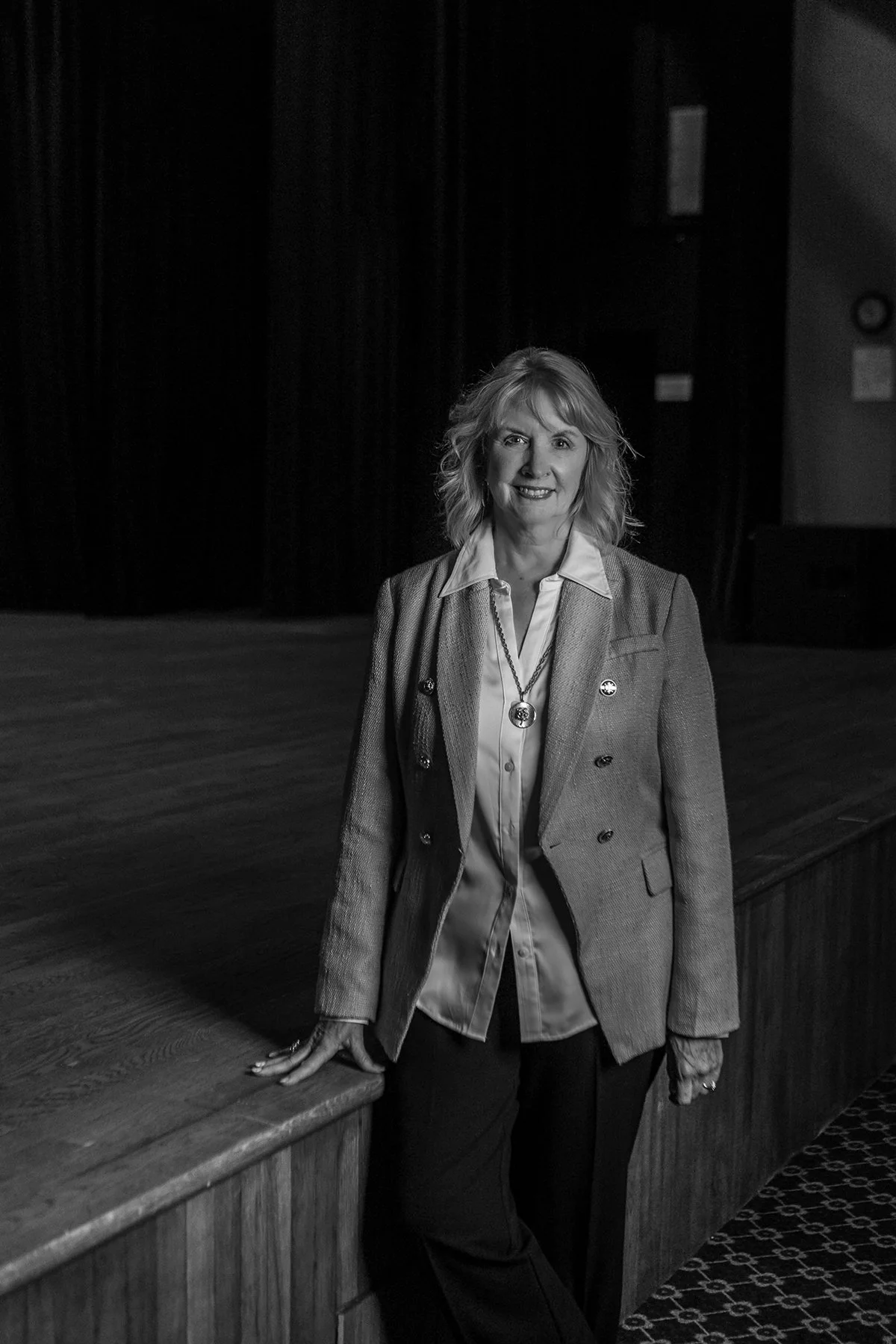

In March of 2015, the Board of Directors of the State Fair of West Virginia unanimously named Kelly Tuckwiller Collins to the position of CEO. An extensive nationwide search for the right candidate led the board right back to its own home—Collins is a Greenbrier County native and was raised, as many Greenbrier Countians are, showing livestock year in and year out.

These days, she’s a champion of the State Fair’s forward progress. Her own background is in marketing, journalism, and, no surprise, fair management. She’s a graduate of the International Association of Fairs and Expos Institute of Fair Management (a mouthful, but a highly respected program nationwide) and has experience with committees and boards with IAFE, the West Virginia Association of Fairs and Festivals, and more.

But more than that, she’s been a champion of the State Fair of West Virginia since she was named CEO, despite being held in a small state, SFWV is one of the most well-respected fairs in the country, spoken about in the same lists as state fairs in Minnesota and Texas. Both are huge and hugely popular, but under Collins’ leadership, West Virginia has been making some of those same lists.

Despite the success of the State Fair, the excitement of concerts, the hype around certain iconic Fair foods—the drive for all of this still stems from the same place it did a hundred years ago:

“When our ancestors and local family members started the Fair back in 1921 as the Greenbrier Valley Fair, they did so to promote agriculture, of course,” Collins says, “but to also spur the local economy and bring the community together. And I still think that’s one of our biggest goals today. We want to teach the story of agriculture, but we really want to bring the community together in a common place.”

Picture this: You’re traveling slowly. The year is 1921, and no one has even considered grading the corridors that will one day become the Interstate highway system. If you’re lucky, you’re in a vehicle that moves at about 25 miles per hour, but it’s not unlikely that you’re traveling by horseback.

Admission is 75 cents for the daytime—that’s more than $13 adjusted to 2025—and 50 cents at night. Your most show-worthy handmade items are carefully wrapped in newspaper or stored in crates. (“Exhibits of farm products,” to reiterate from the following year’s write-up in the local paper, “are bewilderingly large.”)

Perhaps your children are looking forward to Harry Wheadon’s Sensational Novelty Slack Wire Act, the first national entertainer to be contracted for the Greenbrier Valley Fair by its new Board of Directors. Pain’s Fireworks are contracted for August 22 and 23, the first two nights of the Fair, and for Thursday, August 25, the next to last night.

Beyond the steady advances of time and technology, not much has changed for the State Fair of West Virginia, which was codified under that name in 1946, after a four-year gap to account for World War II. Under board members whose grand- and great-grandchildren are still living in the Greenbrier Valley today, the Fair still operates with a drive for community and agriculture.

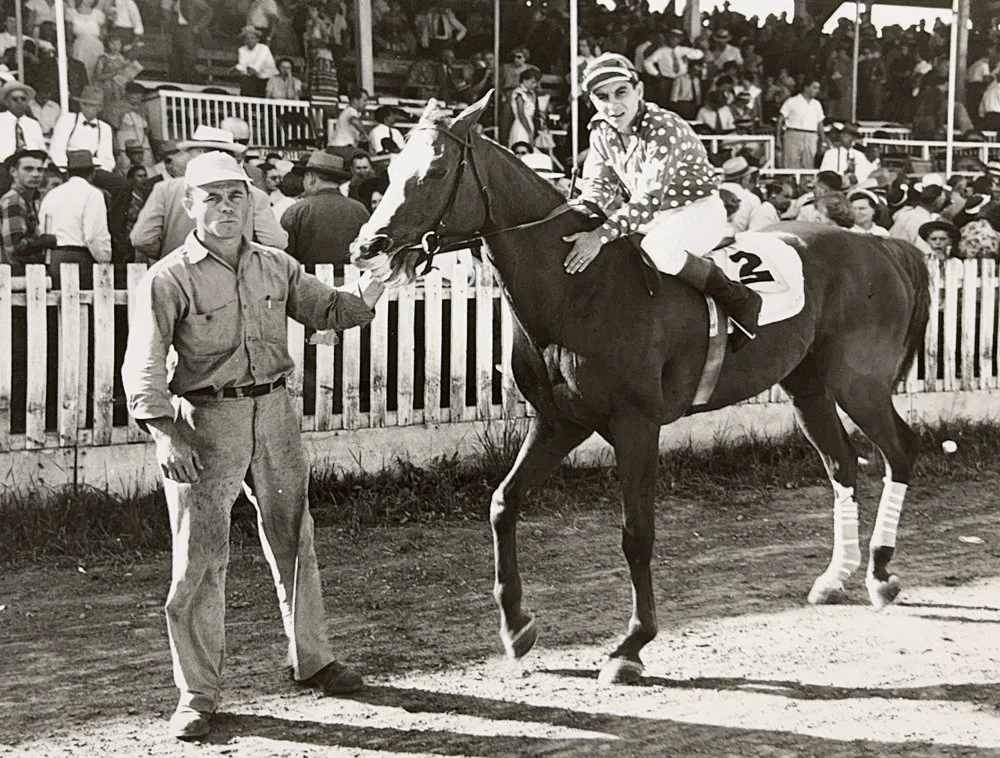

“It was the same event in 1921 as it is today,” Collins says. “We started with a racetrack and a few barns and we’ve grown from there, but it was really that foundation that our family members laid out for the Greenbrier Valley Fair.

“There’s always been the basis of competition to the Fair, but we’ve really grown that over the last hundred years to be what it is today, and it’s a chance for people from across the state and the region. [People come from all over the East Coast] to show off their agriculture and Home, Arts, and Gardens displays – with the needlework and the food and the flowers and vegetables and arts and crafts to showcase that work as well. In 1921 when we created it, of course you had the animals, but you also had some great bakers and home ec. projects that people could put together and show off their skills.”

When former State Fair Manager Marlene Jolliffe entered the world of the Fair, she started not in the show rings or the handcrafts exhibits—she began in the parking lot. The Greenbrier East High School band and choral programs have parked cars in the free parking lot across Route 219 from the fairgrounds for decades, and Jolliffe, a native of Alta, spent her fair share of time directing those countless vehicles into as orderly a pattern as can be managed.

“My senior year, I was working at Western Sizzling, and Ed Rock,” the State Fair manager at the time, and his wife, Sue, “came in and I waited on them. I almost spilled a steak in his lap,” Jolliffe recalls. “And we had a good laugh and we chatted, and about three days after that, he called and said, ‘Would you like to work in the office at the Fair?’”

She shares that she was excited and slightly surprised to hear the offer from Rock—she didn’t feel as though she was very connected to “Fair people.” But the impression she left on Ed Rock was clear.

“I worked for Glenna Hefner handwriting hundreds of entry tags! Spent a week doing that. And then Ed said, ‘she’s too good. I’m going to have her sell tickets.’” Hefner, who passed away in 2022, was a fixture in the State Fair administrative offices – over her 40-plus years working for the Fair, her influence could be seen, if one cared to look, in every part of State Fair goings-on, and indeed can still be found to this day.

A far cry from handwriting entry tickets, one of Jolliffe’s biggest pushes for the State Fair came even before she was named to the manager position. She was a major advocate for modernizing the Fair’s systems as technology began to evolve rapidly and exponentially.

“It was a very fun journey. I remember from day one being very passionate about things we should be doing better,” Jolliffe says. “Technology was kind of starting to come along, but I pushed Ed hard over the years—we needed computerization, and he hated computers.”

But her efforts were successful. From her official start date as Assistant Manager in August of 1981 to her move to Virginia in 2015, she spearheaded marketing, advance ticket sales, the leap to more and more efficient technology, and the Fair’s first change of carnivals—from National Exposition, Inc., to Reithoffer Shows in 1990—in almost a decade.

“And our joke! I taught Ed Rock how to play Solitaire on a rainy Fair night,” Jolliffe says with a particular kind of humorous pride, “and he was so hooked that we knew when we couldn’t find him, he was in the middle office, playing Solitaire.”

A hundred years is a long time to keep an event like the State Fair running—and two hundred years is even longer. It requires money, time, and forward thinking to set up a business – and an event! – for that kind of long-term commitment. Nevertheless, that’s what the State Fair is preparing to do, even as the event celebrates its 100th year in 2025.

Collins, who has championed the Fair since she was named CEO (and before), has a passionate speech to give about the subject:

“My predecessor and the former CEO of the State Fair, Marlene Jolliffe was really big on the idea that our role as fair employees are caretakers of our events. And I don’t think that she could be any more right on that—you truly feel like you have this 100-year legacy in your hands and it’s your job to make sure that it’s going to last, and stand for the next 100 years.

Kelly Collins, Ed Rock, and Marlene Joliffe

“We’re a very small staff—less than 10 year round, and five of those are maintenance. So with the maintenance guys keeping the properties physically intact, our job in administration is the logistics and the planning, and to get people through the gates to keep on making memories for the next 100 years. That’s really our goal.”

She also talks about the responsibility she’s shouldered as manager of the Fair, a role with a surprisingly short history over the last century.

“I’m the fourth manager out of a 100-year history, which was a little bit of pressure when I took the job, to be honest, because the folks that came before me did such a good job. And I think if you look back from Tommy Sydenstricker to Ed Rock to Marlene, each of them played such an important role in taking the Fair to the next level.

“Tommy Sydenstricker and Ross Tuckwiller and the original staff and board of directors did an amazing job at creating this event. Ed Rock took it to another level. Marlene took us to a new century. There’s such a strong group of individuals that I think this community was really lucky to have.”

Some people are still surprised to learn that the State Fair is a charitable nonprofit organization—through an endowment fund created in 2006, the Fair business supports youth education and agriculture with scholarships, education partnerships, and more. The annual $1,000 scholarships go to five students for four years of higher education, totaling $20,000 earmarked each year just for scholarship recipients.

Though it wasn’t always a nonprofit, the State Fair has never been out to make some boundless fortune each year—every dollar not put back into the grounds or the events held there goes back into the community as part of the endowment and other support projects.

“We aren’t out to make millions of dollars. That’s not what we want to do. And of course, we do see millions of dollars come through, but that’s all put back into the community,” Collins says. “If there’s any left over, we use that to upgrade the fairgrounds. We’re actually getting ready to start a $30 million master plan to ensure that the infrastructure of the Fair withstands the next 100 years. So we’re focusing on the past a hundred years, but we’re quickly going to turn over to the next a hundred years once the Fair is over to make sure that we are preserving the fairgrounds for the next generation.”

State Fair attendance is a yearly tradition for families across West Virginia, and for no small number of people who travel for the event—homecoming for some, a change of scenery for others, but a can’t-miss event for all.

One of the biggest draws is bringing your kids, the same way you were packed into the car with sunscreen and extra bottles of water (often frozen, to melt down and cool the searing August afternoons) and contingency plans for when someone inevitably got separated from the group. (RIP to “The Tree” – the iconic meeting spot at the center of the Fairgrounds was changed forever in 2020 when part of the huge tree came crashing down, forcing Fair staff to remove the rest for safety reasons. Accounts of the Tree date back almost to the beginning of the Fair’s history, even when it was still known as the Greenbrier Valley Fair, and can be seen in photos as early as the 1930s. Even then, people met up under its branches for a break from the sun.)

For some families, introducing the kids to the Fair is the whole point—adding another layer of family traditions that are starting to now continue for four, five, six generations of fairgoers.

Both Collins and Jolliffe can attest to the power of going to the State Fair with their kids.

“Now that I have kids, I can see it even more,” Collins says of the way that family tradition becomes more important when you’ve grown up in the Fair and are now bringing your own kids. Collins’ own children are growing up close to the Fair and their presence makes the whole event extra special for their mom.

“I have an eight-year-old and twin six-year-olds,” she says, “and to see the Fair through their eyes is a whole different view.”

Jolliffe’s experience is similar—though she didn’t grow up close to the State Fair in the same way Collins did, her love for the event has been changed by experiencing it from the outside, with her family, and by raising her kids with the State Fair.

“I took one year off and that’s when Frank and I adopted our kids,” she says. “And that year and a half off really was just one of the best things I ever did, because it gave me an outside perspective of what it feels like to not be involved with the Fair and see it go through setup and experience it with kids.”

The 100th year may just be the best time to start going to the State Fair if—or bringing someone for the first time. The administration, board, and membership have been pulling together for a few years now to make the celebration appropriately bombastic. With special concerts, extraordinary light shows, and an enhanced version of the same Fair energy everyone knows and loves, the attraction is set to be an even bigger show than usual.

At the same time, the cultural and agricultural heart of the event is also beating stronger than ever this year.

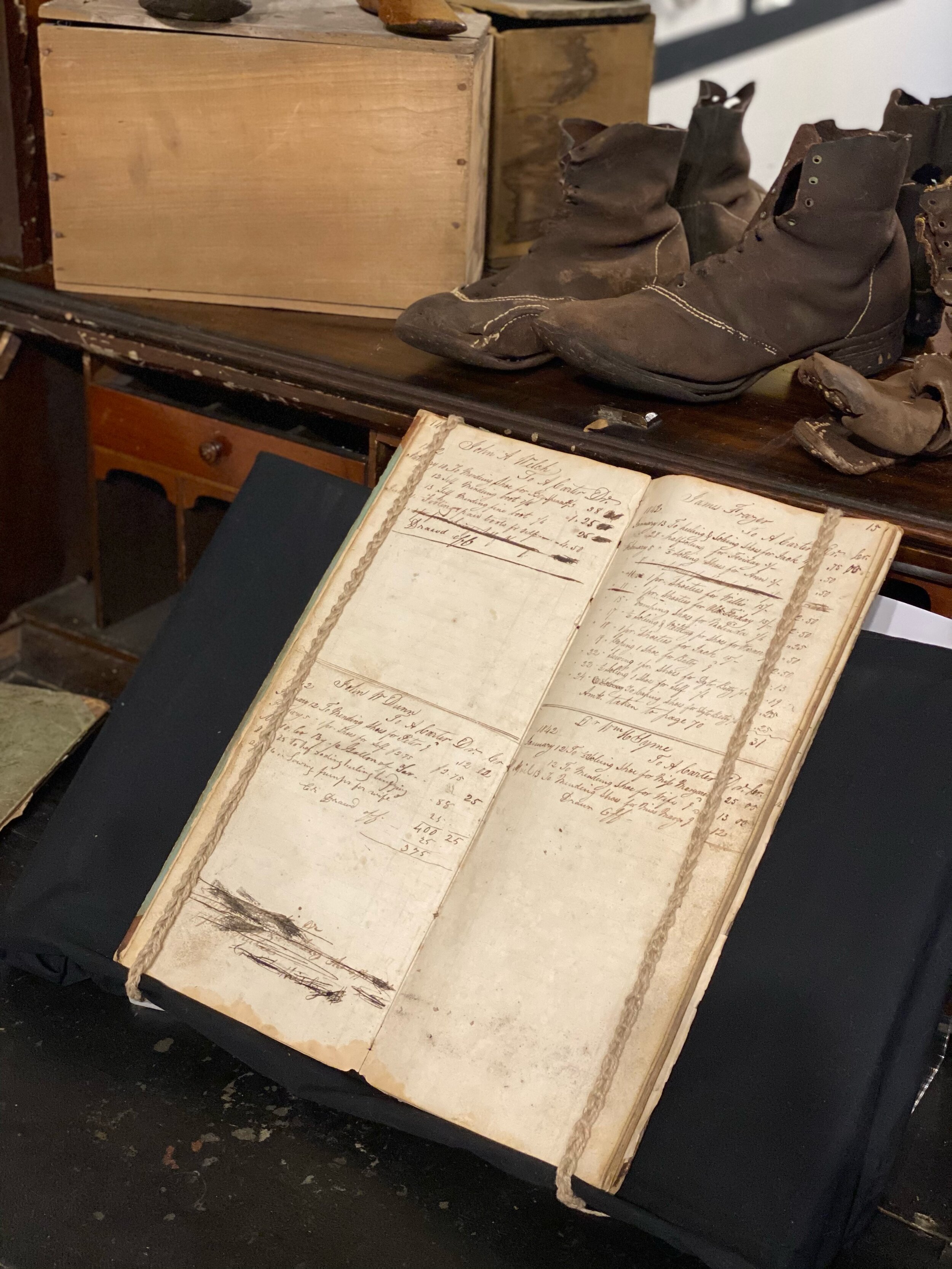

In the far north corner of the fairgrounds, where Fair Street meets the southbound lanes of Route 219, lies an exhibition alley the Fair calls “Heritage Corner.” There, the Master Gardeners show off the Heritage Garden, craftspeople show off their skills with blacksmithing, and antique tractors sit proudly next to sleek modern counterparts.

Near the fence, there’s a tiny, older building—it’s the museum, and it’s brimming with Fair history. Over the last couple of years (and longer!), the State Fair has been pouring time and energy into curating this trove of hyper-regional history, and this year is the perfect time to visit, whether you’ve seen it before or are crossing that threshold for the first time.

“We’ve been planning this Fair for probably two years now, just pulling together some of the history,” Collins says—though two years may be underselling it. “There’s a lot of history over the last hundred years and a lot of big events that have happened, and you really [start to] focus on that portion of the Fair at the big milestones like 50th annual Fair, and the 75th.

“So now that we’re at 100, it’s time to go back and add to the history,” she continues. “Even over the last five to 10 years, we’ve had a lot of things that have happened that needed to be added—I mean, we had a cancel a Fair in 2020, and we’ve only done that five times in our hundred years.”

This is also a great time to support events like the State Fair which bring people together and give back to the community. Jolliffe, who now works with the Virginia State Fair, has seen trends go up and down over her nearly 40 years in the business—and it’s getting harder, not easier, to manage events of this kind.

“I say every day, it’s the hardest time in my entire career to be in this event business. It’s just very, very hard. Consumers are hard. The growth of social media,” she notes in particular, “has been a blessing and a curse. You have access to big audiences, but they can also just criticize you. And if they don’t like something, they’re very vocal. But you don’t make it another hundred years without an open mind that things are going to have to evolve.”

The tradition of community, though, is what makes even the hard days worth it, according to Collins.

“We’ve see that people are entering exhibits because their parents did or because their grandparents did, and it’s really a tradition that’s passed down a year to year,” she says. “It’s always exciting when you get somebody who’s never entered exhibits into the Fair. Part of the job is to honor the tradition, but also invite new people into the tradition. We don’t want to gatekeep the secret of the State Fair and how great we know it is. We want more people to see it.”

At 100 years of the State Fair, it’s more important than ever to honor the history that brought the event and the region to this point, while looking ahead to the future. This event has grown under careful stewardship from a regional fair attracting 15,000 people to the region once a year to a major economic driver for the area—over the course of the year, the State Fair business brings around $2.5 million to the state of West Virginia, but more importantly, it takes care of the kids who have loved it from day one.

“Several of the folks that are currently working for us, myself included, we showed livestock growing up, and the money that we earned from showing our animals at the Fair and selling them in the auction, we purchased cars with it, we went to college with that money, Collins explains. “So we know individually how important it is, but to see it and on this side of the Fair now and see the kids getting the same opportunity, and to see the small artisan that makes their entire budget for the year during the State Fair, that’s really important to us and what we do today.”

Jolliffe, who still loves the State Fair of West Virginia as much as she did when she was managing it, has a similar outlook.

“I asked a survey question last year—‘Do you feel the Fair is important family tradition?’ And 76 percent of respondents said yes. And I think that’s what will keep the Fair going for another hundred years.”