Pouring Community, One Glass at a Time

Story by Kara Vaughan | Photography by Josh Baldwin

On a quiet ridge in Monroe County, Old World Libations has become more than a winery—it’s a gathering place where neighbors, travelers, and families all feel at home. Guided by Scott and April Ernst, every bottle, story, and Friday night gathering reflects their vision of creating a true community living room.

On a Friday evening in Monroe County, the vineyard lights glow long before the stars appear. Pickup trucks crunch into the gravel lot, a car with out-of-state plates nose in beside them, and children tumble from back seats, already darting toward the creek that runs behind the vines. Neighbors wave across the parking lot, greeting one another with the ease of family. A guitarist tunes up on the porch. Inside, bottles are uncorked, glasses catch the last of the sunset, and laughter carries into the valley.

This is Old World Libations—or simply “OWL,” as locals call it—a winery, cidery, and meadery tucked into the folds of Monroe County. But for many, it is something more: a gathering place, a community hub, a comfort—the living room of the county. Scott and April Ernst designed it that way. With intention, warmth, and a deep love for the land they call home.

When I arrived, it was a quieter hour, between harvest days, when the land seemed to draw in a deep breath between labors. The cicadas kept their steady chorus, their voices rising and falling like the pulse of late summer. Sunlight spilled lazily across the hills, catching on the drifting leaves that spiraled down in slow motion, golden in the fading light. The air carried the scent of ripened grapes, mingled with the sweetness of cut grass and the faint mineral tang of the creek nearby. Everything felt suspended, as though time itself had paused to admire the stillness.

At the grand front door, I was greeted by Bailey—the farm pup and unofficial keeper of first impressions. Tail wagging and eyes bright, she howled in excitement. Her presence set the tone—this was not a place of stiff introductions or rehearsed hospitality, but one of genuine warmth, where even the dog seemed delighted to fold you into the family. As I made my way through the tasting room and to the back porch door, I could see Scott and April’s passion in every detail. There was a light breeze that carried the perfume of ripe earth and golden sun rays over the wooden back porch.

“We knew what we wanted...The land needed to be tillable, affordable, rural, and there would ideally be a waterway. Most importantly, there would be a strong community presence...This was one of the very few places that hit all the check marks,”

Wildflowers swayed along Indian Creek, a waterway once traveled by Native Americans. Adirondack chairs, shifted and rearranged, marked where families had gathered and couples had lingered. Stacks of smooth river stones, built by children and dreamers, shimmered at the water’s edge—tiny, impermanent monuments to shared time. Water rushed along the creek, mirroring the faces of those who once walked its banks and those who now carried their memory forward. OWL, I realized, was less a curated space than a place shaped by everyone who walked its paths.

The Ernsts’ story didn’t begin with grapes or apples. It began with two teenagers growing up in West Virginia. “We are both from West Virginia,” Scott explained. “We were high school sweethearts. We went through college together, and then I went into the military.” For more than twenty years, the Ernsts moved from base to base with the U.S. Air Force, living in around thirteen different places across the U.S. and around the world. Scott acted as a liaison between the Army and Air Force, translating combat objectives into aerial missions.

“My job was to take what the Army wanted to accomplish from a combat perspective and translate that to Air Force speak to accomplish missions,” he said. “It kept me on my feet and I was always active.” April, meanwhile, dove headfirst into each new community. “We knew we’d only be there six months or a year,” Scott recalled, “so we made the most of it. April especially—she’s an extrovert. Meeting new people, building connections, becoming part of the place—that became our way of life.” When Scott retired, the couple faced a question: what now? For Scott, the answer needed movement and purpose; for April, it needed people and conversation. “That’s when the vineyard idea came in,” Scott shared. “I needed the physical work to stay active. April needed the community. A winery gave us both.”

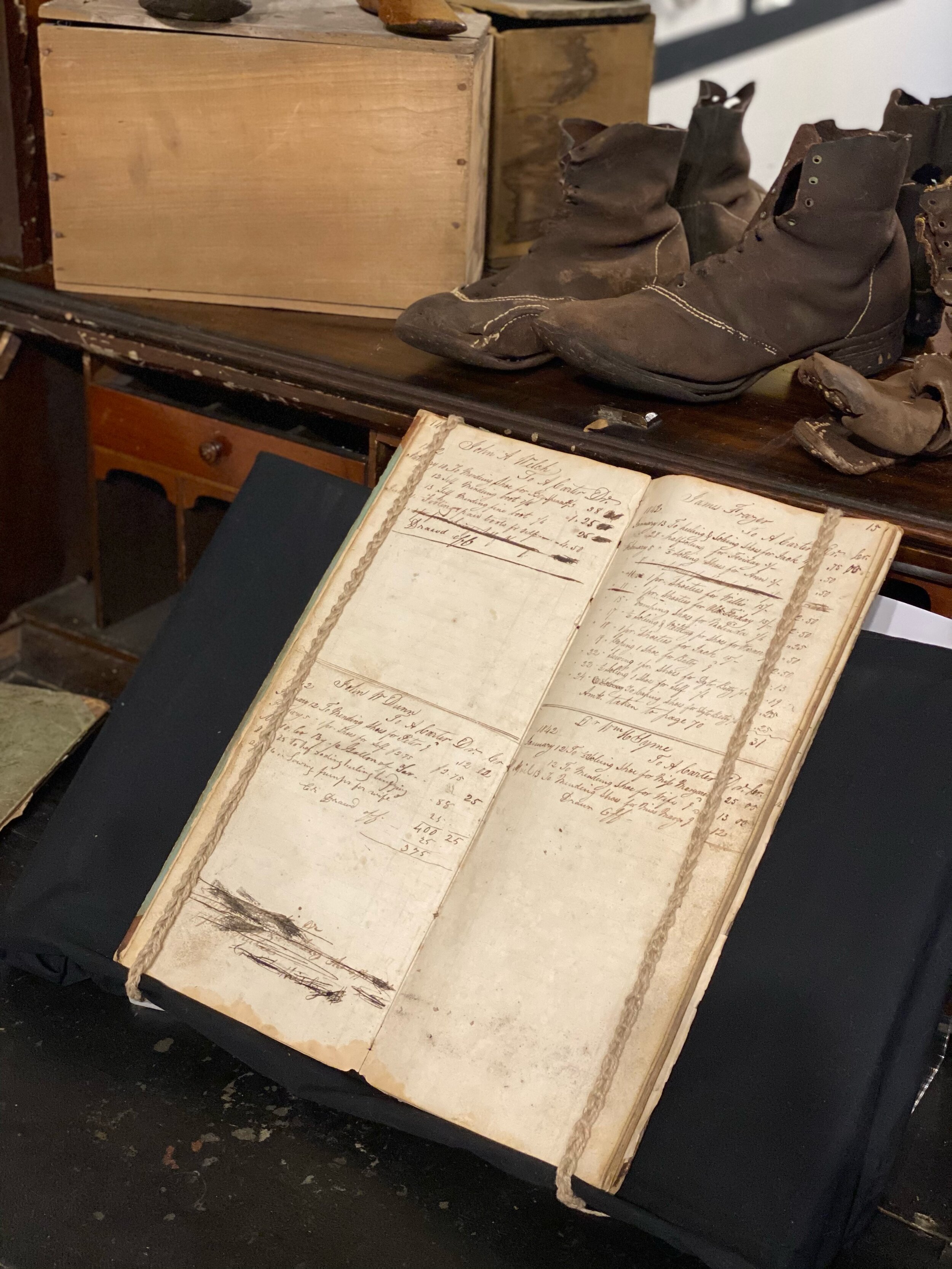

As I wandered deeper into the space and into our conversation, the silence of the property wasn’t empty but layered, humming with memory. I could almost hear the echoes of nights past—guitars strumming on the porch, voices tangled in laughter, glasses raised in toasts that carried more gratitude than words could hold. The room held these ghosts tenderly, like a shell still resonating with the ocean after the tide had gone. Even in the stillness, the walls seemed to draw nearer, carrying a quiet invitation to belong. With humility and grace, Scott reflected on the winding journey that had led them to this season of fulfillment. Like the dream he and April shared, the search for land had been intentional, every step taken with care and purpose.

“We knew what we wanted,” Scott explained. “The land needed to be tillable, affordable, rural, and there would ideally be a waterway. Most importantly, there would be a strong community presence.” They found all of it in Monroe County. “This was one of the very few places that hit all the check marks,” Scott said. “From the start, the locals supported us—even when we were just running tastings out of the house, which was not traditional at all. But people showed up, they encouraged us, and it grew from there.” That early support planted the seeds of something bigger: not just a winery, but a community hub.

Even the name reflected their vision. The Ernsts spent five years living in Germany, where they first discovered wine culture. “We went there not knowing much about wine,” Scott admitted. “But the wineries in Europe were so different. They were open and welcoming. Kids were running around. You could walk the production area and the fields. Wine was on the table at every meal—it wasn’t this pretentious, high-class experience like it sometimes feels in America.”

They wanted to recreate that openness in Monroe County.

“Libations just fit,” Scott explained. “We were more than a winery—we made mead and cider too. And the word ‘libation’ has ancient ties to the ritualistic pouring of offerings to the gods, which resembled an act of gratitude. We really felt like that name fit all that we offered and had meaningful roots. Plus, we took our time here. No additives to speed fermentation, no shortcuts. We’d rather let the wine age naturally. It was more authentic.” That philosophy carried into the vineyard itself, where every planting was chosen with the same patience and intention.

At OWL, every batch rests for at least a year, often closer to eighteen months. That patience lets the ingredients weave together naturally, creating a harmony of flavors that can’t be replicated anywhere else. Rows of vines stretched across OWL’s property. They offer six different grape variations: three reds—Lyon Millot, St. Croix, St. Vincent—and three whites—Vignoles, Traminette, La Crescent.

“These were the varieties that grew best here,” Scott said. “We could plant Cabernet Sauvignon, but then people would compare it to a California Cab. Or Riesling, and it’d be compared to a German Riesling. Why invite that? By planting grapes that grow the best in this soil, we create wines that stand on their own.”

Each grape reflected Monroe County’s microclimate, with many wines carrying a bright note of apricot. “Honestly, I can’t explain why,” Scott admitted with a grin. “It’s just the personality of this land.” The result? Wines that are crisp, approachable, and distinctive. These libations are easy to drink, but layered with character—each bottle a reflection of this place alone. Scott and April embraced the land’s charm, weaving each bottle back to its roots with intention and care.

The Ernsts don’t just bottle wine—they bottle stories. “Most of our labels are tied back to a season of our lives,” Scott said. “They connect us to the farm and the farm to the wine.”

Empty Nest was harvested the day April drove their youngest daughter to college. The label depicts two ravens flying from a nest, representing their children leaving home. Prosper celebrates the moment the winery truly felt sustainable. It reflected the time they knew this venture would work. Its label shows an apple tree with Scott and April’s initials carved into the base of the trunk with a heart engraved around them.

Weary Traveler is a cider named after phantom footsteps once heard along an old trail on their land. “Our driveway used to be an old wagon road and before that, it was a dirt road used by Native Americans,” Scott explained. “One fall evening, we swore we heard footsteps in the leaves. Clear as day. I crawled through the brush to listen, and the footsteps stopped. There was no one there. When I backed off, they started again.” Scott’s voice softened, carrying gratitude for the land’s rich history. Each bottle carries memory, folklore, or a milestone—blending personal history with the spirit of the land.

On Friday nights, OWL transforms into what the Ernsts had always envisioned—a living room for Monroe County. The space hums with life, overflowing with locals who seem to bring their own warmth as much as they came seeking it. “I don’t know if it’s our vibe that draws people here, or if folks simply carry it with them,” Scott mused, “but the atmosphere is always comforting.” The room feels less like a tasting room and more like a front porch that stretched wide enough to gather an entire county. Farmers drift in after long days cutting hay, dust still clinging to their boots. Travelers find rest, their voices mingling easily with the steady rhythm of conversation. Children chase fireflies and splash in the creek, their laughter rising like music against the song of cicadas.

April and Scott float from table to table, weaving threads of connection as naturally as pouring wine. Strangers are introduced, stories are shared, and by the evening’s end, a newcomer might leave knowing ten new names, each one spoken with the ease of kinship. Conversations meander—from music to farming, from trades to tales of the land—neighbors trade contractor tips as readily as they swap recipes or vineyard lore.

Scott and April Ernst

“Saturdays and Sundays are slower-paced. These are the days we can really talk with people,” Scott said. Guests sip by the river, wander the vineyard rows, or settle into Adirondack chairs. “We enjoyed talking about the grapes and how each one reflects this land. Not a lot of people realize this, but a lot of wineries don’t use their own grapes in their wine. What you taste here comes from this soil and is a labor of love. You won’t find it anywhere else.”

While grapes anchor the vineyard, OWL’s offerings go further. Mead adds a Nordic note, fermented from honey. Ciders, often served on tap, rotate seasonally. “Midsummer Fling is a favorite,” Scott said. “It drinks like a hard ginger ale. But really, everything sells well. We made the menu broad so there is something for everyone—sweet, dry, crisp, bold. That was intentional.” Most sales happened face to face, though cases can be ordered online. “It works better in person,” Scott explained. “This place is about connection and conversation.”

“My favorite event is probably our annual Cider Festival, held the fourth weekend in October. It really captures the essence of OWL,” Scott shared. Vendors set up in the grass, musicians play, food trucks serve meals, and families gather. The star is the cider—crushed and pressed the day before, sold fresh and unpasteurized. “When it’s gone, it’s gone,” Scott said. Children line up to toss apples into the grinder, sticky-fingered and grinning. Adults sip the cloudy juice, savoring its refreshing sweetness. “To my knowledge,” Scott added, “we are the only place around doing it completely unpasteurized. That’s what makes it special.” OWL also partners with local artisans—potters, woodworkers, weavers—who display their work and craft on event days. These collaborations extend OWL’s role as more than a winery; it is a stage where the county’s creativity comes alive.

This is the spirit of Old World Libations: not just a winery, but a reflection of Monroe County itself—patient, rooted, and welcoming. “It’s a community center. A place where people feel at home,” Scott said. And as the lights hum into the night, Old World Libations carries on—the living room of Monroe County, where land, wine, and community flow together as one.